Support in-depth Calgary journalism.

Sign Me Up!We connect Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism—but can't do this alone! We rely on our readers and listeners to fund our work. Join us by becoming a Sprawl member today!

Jason Kenney has been a politician for almost his entire adult life. He’s been an elected representative for more than two decades, both federally and provincially. If political success comes down to selling one’s self to voters, Kenney has shown an ability and willingness to shift his pitch and image as needed.

As Stephen Harper’s immigration minister, he shaped a persona as a forward-looking, savvy glad-hander of emigres from countries with conservative cultures. As prospective premier of Alberta, Kenney has shifted to a pickup-driving everyman with populist outsider appeal.

To better understand the man behind these personas—the man who seeks to be Alberta’s next premier—The Sprawl presents a two-part investigation of Kenney's political roots, beginning in San Francisco during the late 1980s. (Read Part 1 here.)

On December 1, 2018, two clips of UCP leader Jason Kenney were posted on Twitter. The first was from Kenney himself, a video marking World AIDS Day in which he says: “This is a disease I first saw first-hand volunteering at a hospice in San Francisco back in the 1980s.”

It’s a reference Kenney has made several times before, highlighting that “a young Jason Kenney spent his time washing bloody sheets” at the Gift of Love Hospice when he was a student at the University of San Francisco.

Later that day a second clip was posted, this one by a lawyer named Kyle Morrow. It was an audio-only clip (video surfaced later) of Kenney speaking to Canadian Alliance supporters in 2000. In the clip, Kenney brags about his role in helping to overturn a domestic partnership law as a student activist at the University of San Francisco in the early 1990s:

I became president of the pro-life group at my campus, and helped to lead an ultimately successful initiative petition, which led to a referendum which overturned the first gay spousal law in North America in 1989 in San Francisco. [In the video version, Kenney grins here.] I fought a lot of battles there, and in the process of those battles, ended up coming closer to the heart of the church in a spiritual sense as well.

That law would have provided various benefits to same-sex couples who registered as partners—including hospital visitation rights, especially significant during the AIDS crisis that, at its worst, was killing over 1,400 San Franciscans annually.

The audio clip was damaging for Kenney, landing as it did on World AIDS Day. He didn’t exactly apologize, telling reporters: “Sure, there are things that I've done and said in my life that I regret.”

Asked if that included his comments on the tape, he replied, “Sure,” and said his public stances on LGBTQ+ issues since then demonstrated he has changed.

It’s entirely normal and healthy for people’s views to evolve over time. The question isn’t whether the 32-year-old Kenney in the second video is the same as the 50-year-old Kenney running for office. It’s how he went from bragging about helping prevent gay men from visiting their dying partners to boasting about volunteering in a San Francisco hospice for AIDS patients.

Is it genuine reformation? Or political convenience?

Domestic partnership in San Francisco didn’t come easily. It was a fight that stretched over most of the 1980s.

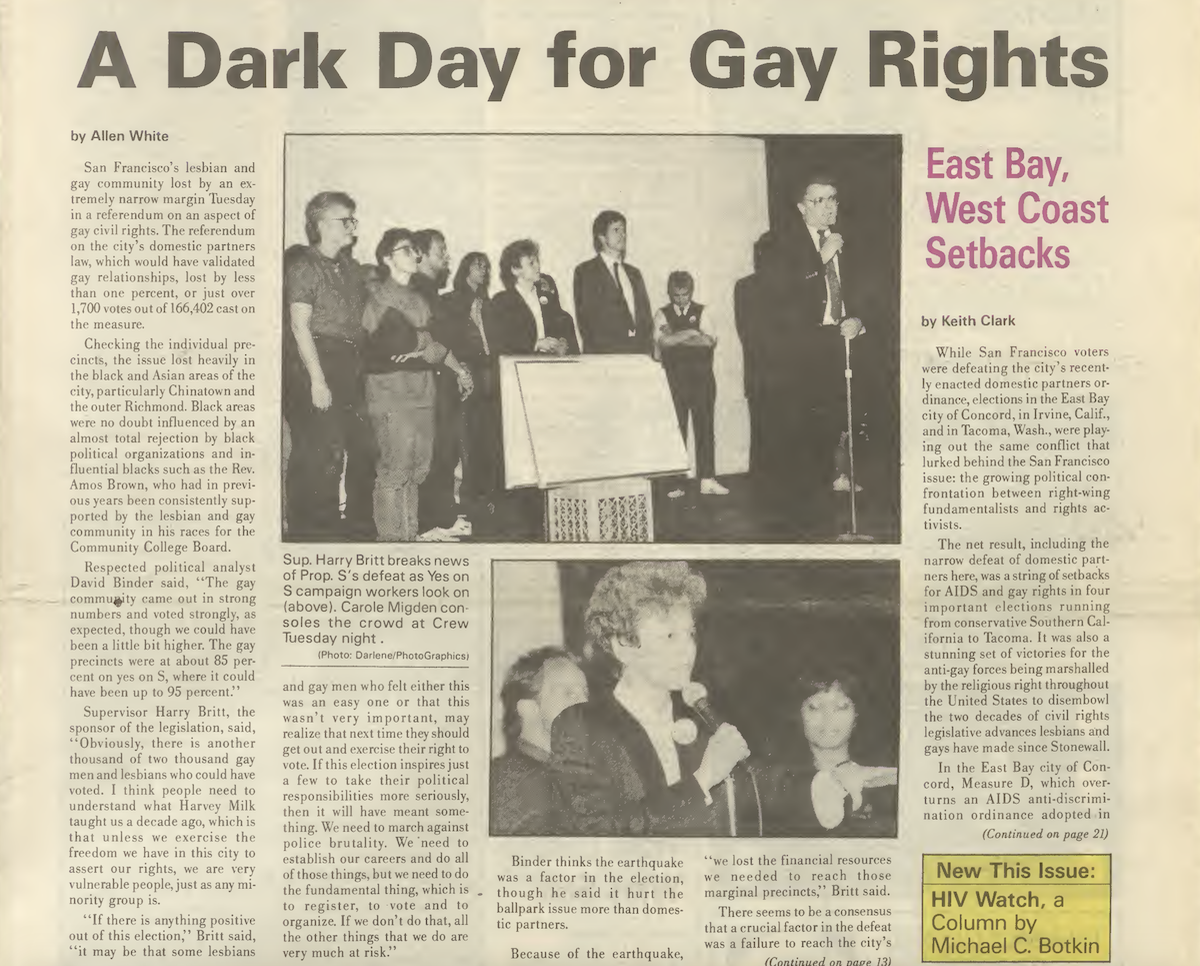

In May 1989, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted unanimously in favour of domestic partnership legislation that extended to same-sex couples many significant benefits enjoyed by straight married couples.

“If my heart tells me and your heart tells you that we should share our lives together and care for one another, the government has no business telling us we will be discriminated against,” board president Harry Britt said at the time.

Context is important for understanding the significance of this ordinance. San Francisco has long been famous for its queer communities, and 15% of its residents identify as gay or lesbian—higher than any other major U.S. city.

If my heart tells me and your heart tells you that we should share our lives together and care for one another, the government has no business telling us we will be discriminated against.

HIV/AIDS became a deadly force in the 1980s, with men who have sex with men being especially at risk. By 1989, thousands of San Franciscans had died as a result of the disease. The gay weekly Bay Area Reporter from this period has many grim pages filled with obituaries and advertisements for funeral services.

At the same time, the push to recognize individual rights led to a push for relationship rights, too. Married couples enjoyed many benefits under the law that same-sex couples, who could not marry, were denied. But as these movements gained steam, so did the opposition.

As historian George Chauncey noted in his book Why Marriage?, “The spread of AIDS and the steady escalation of gay issues at the local level fuelled a growing polarization of the nation in the 1980s.” Rather than normalize the subject of LGBTQ+ rights, the heightened visibility and misconceptions only galvanized anti-LGBTQ+ forces.

Victories, according to Chauncey, were “often more difficult to achieve than they had been in the 1970s.”

In San Francisco, the unanimous vote in May followed a similar attempt in 1982 that was vetoed by Mayor Dianne Feinstein. In the intervening years, other Bay Area cities like Berkeley and West Hollywood had passed domestic partner legislation.

Now San Francisco was set to join them.

But an initiative led by opponents to the ordinance, especially the Catholic church and religious right, forced the issue to a referendum by collecting 27,000 petition signatures.

That’s the initiative that Kenney boasts about being involved with in the video.

It’s not clear exactly what Kenney’s specific role was in petitioning for the referendum. The UCP did not grant The Sprawl’s request for an interview with Kenney. In an email, Kenney said his role was limited to putting up posters and distributing flyers—which raises the question of why he was taking credit for helping “to lead an ultimately successful initiative petition.”

As a student at the St. Ignatius Institute at the University of San Francisco—which the San Francisco Chronicle called “an ultraconservative enclave on the Jesuit-run campus”—Kenney was involved in various activist causes aligned with the religious far-right, including an infamous battle over a student pro-choice petition that he threatened to escalate all the way to church authorities in Rome.

Kenney said his role was limited to putting up posters and distributing flyers — which raises the question of why he was taking credit for helping “to lead an ultimately successful initiative petition.”

Reporting on the movement to force a referendum, the San Francisco Examiner noted that the Archdiocese of San Francisco had used its resources to distribute and coordinate the petitions. The Bay Area Reporter observed that “the local Catholic Church has been the most vocal opponent of the ordinance.”

Polling showed a majority of San Francisco residents supported the domestic partnership legislation. But as Harry Britt, the sponsor of the law, pointed out, “The profile of the electorate that votes in an off-year election is extremely conservative.”

The efforts of Kenney and the religious right would narrowly defeat the measure by fewer than 2,000 votes.

Church groups called the measure a ''bizarre social experiment'' and an attack on the family that would erode traditional values. Opponents also argued that it paved the way for extending health and pension benefits to unmarried couples, potentially costing taxpayers thousands of dollars.

The Roman Catholic Church distributed 25,000 leaflets challenging the measure

"The story here is the hidden power of church groups to affect an election like this,'' said Dick Pabich, the measure's campaign manager.

—New York Times, November 9, 1989

The victory would be short lived, as the legislation would be put to voters again the following year and succeed. In 1999, California legislators enacted a modest state-wide domestic partnership law, which was further expanded in later years.

This saga is a clear-cut tale of Kenney vigorously opposing LGBTQ+ rights.

But the other story he tells is one of tolerance and compassion for the LGBTQ+ community—specifically, those he helped care for while a student in San Francisco.

The Gift of Love Hospice was located in the southern part of San Francisco. Operated by Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity organization, the facility cared for homeless men suffering from HIV/AIDS.

To this day, Kenney describes his experience volunteering there in glowing terms.

“I was transformed,” he said in a 2018 Calgary speech, “watching these humble, simple, often uneducated women from the Third World giving their all to men who had often been abandoned by their families and their friends, who were alienated personally and spiritually, filled with anxiety and depression and a terrible disease. I saw many of these men come to be reconciled with themselves, with their families, and spiritually reconciled as well, not through any kind of proselytization, but simply with the witness of completely transformative unconditional love.”

“There is no government program, and nothing in the market, that can be a substitute for that love and what I witnessed and what changed me.”

There’s very little information available about the Gift of Love. Other similar religious-affiliated facilities figure in the news record and local histories of the era. By contrast, the only mention of the Gift of Love in the Bay Area Reporter appears to be in obituaries of the men who died there.

There is no government program, and nothing in the market, that can be a substitute for that love and what I witnessed and what changed me.

One San Franciscan who described himself as being very involved in the local LGBTQ+ community of that period, as well as devoted to researching “HIV-related ephemera from the city,” said he had never heard of the hospice. Upon researching further he realized why.

“The hospice indeed existed, but was was not associated with the LGBTQ+ community; instead, it was a quite small Catholic missionary effort (and therefore by definition not pro-gay),” he wrote to The Sprawl in an email.

As the Los Angeles Times reported in 1990, local healthcare professionals and social workers were concerned about complaints that Gift of Love patients were discouraged from taking their prescribed pain medication. “Moreover, they say, there is an attitude of discomfort or disapproval that the sisters convey, stemming from the Church's condemnation of homosexual activity,” reported the Times.

Perhaps the most notable appearance of the Gift of Love hospice in a text is an unfavourable one. The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice, a scathingly critical essay by the late author Christopher Hitchens, features several anecdotes from women who worked at the San Francisco facility.

The overall impression is of a miserable place oriented less towards the comfort and care of the dying than to a religious notion of suffering for salvation. The women describe men who were “exceptionally depressed” about the nuns denying them simple pleasures like TV or visiting friends. One tells the story of a man who begs a friend to take him in so he can avoid the conditions there.

As his illness worsened, he begged not to be sent back to the Gift of Love “because he knew they didn’t medicate enough, or properly, and was afraid he would have to die without morphine.”

One woman describes the nuns’ practice of deceiving patients in order to baptize them: “Sisters were to ask each person in danger of death if he wanted a ‘ticket to heaven.’ An affirmative reply was to mean consent to baptism. The sister was then to pretend she was just cooling the person’s forehead with a wet cloth, while in fact she was baptizing him, saying quietly the necessary words.”

There’s no reason not to believe that Kenney was volunteering at the Gift of Love, washing bloody sheets as he has stated on multiple occasions. But it’s worth asking what type of organization he was choosing to support, and whether it was as noble as he suggests.

The question remains: which of these two episodes—both of which Kenney has highlighted at different times—best reflects his current thinking?

In emailed responses to questions from The Sprawl, Kenney says he does not stand by his comments in the 2000 video, nor his actions opposing domestic partnership in San Francisco.

He says that his views on same-sex marriage have changed.

Which of these two episodes — both of which Kenney has highlighted at different times — best reflects his current thinking?

“My opposition to such legislation was based on a concern that it would be a precursor to changing the definition of marriage, which I opposed,” rather than “a desire to limit partners from visiting their loved ones in hospitals,” Kenney wrote.

He cites public statements by various other figures, such as Tommy Douglas and Jean Chretien, to demonstrate his argument that “this was the position of virtually every major political party and government in the democratic world at the time… I have been clear for years that I accept the new social, legal and political consensus on the definition of marriage in Canada.”

Kenney says he was volunteering at the Gift of Love during the same period he was fighting the domestic partnership law. “I am quite sure there was no restriction on intimate partners, or anyone else, visiting their loved ones there,” he writes. “It would never have occurred to me to oppose such a thing.”

In 1996, an Angus Reid/Southam poll found Alberta had the strongest opposition in the country to same-sex marriage at 59%. In 2015, a Forum poll found that number had dropped to 33%—still higher than any other province, but a significant 26-point drop nevertheless.

Same-sex marriage became legal in Alberta in 2005, despite the obstinate resistance of Premier Ralph Klein and his Progressive Conservatives.

In between those polls, of course, same-sex marriage became legal in Alberta in 2005, despite the obstinate resistance of Premier Ralph Klein and his Progressive Conservatives.

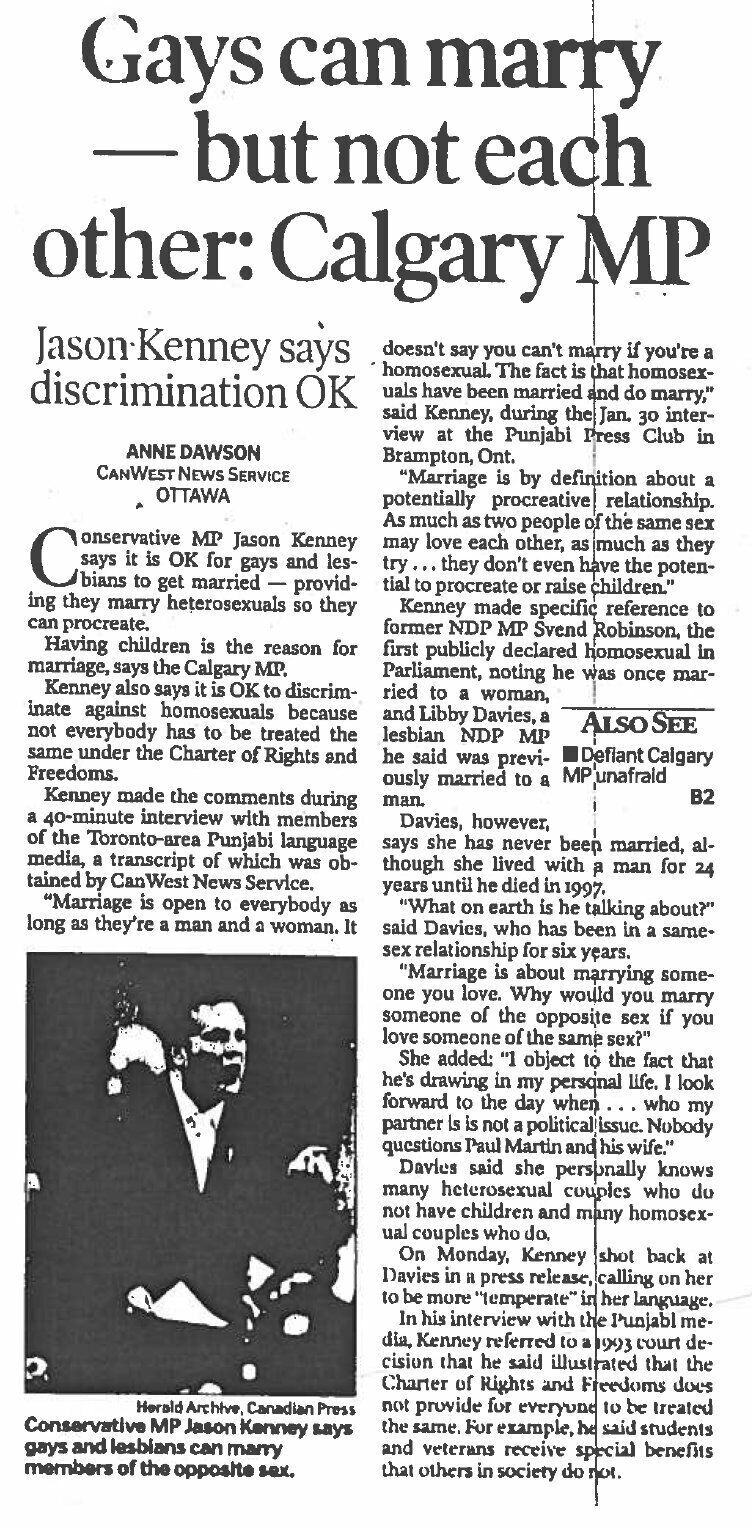

That same year, Kenney infamously said “marriage is by definition about a potentially procreative relationship." Such comments would be political suicide in a general election today.

Much has changed since: LGTBQ+ rights and issues have become a more integral part of our public discourse. Overt bigotry, though still with us, has become more socially unacceptable. And the most outrageous arguments advanced by opponents, including Kenney—that same-sex marriage would undermine “traditional” unions, or that it was a step towards social acceptance of pedophilia—have been exposed as the fallacies they always were.

“I cringe at many things I did or said as a teenager,” Kenney wrote in his email response to The Sprawl. (In fact, he was in his early 20s when he fought his culture war battles in San Francisco.)

He was referring to his opinion piece in the Foghorn, the University of San Francisco student paper, where he compared pro-choice advocates to supporters of pedophilia or the KKK, but the line neatly sums up his general response to many other activities from his past from which he now wishes to distance himself—from opposing the rights of LGBTQ+ people and women, to threatening to take a fight against freedom of speech all the way to the Vatican.

Kenney was in his 30s in that 2000 video where he boasted of his role in overturning critical LGBTQ+ rights legislation. He was not only proud of it then, but knew his partisan conservative audience would be receptive.

The question of how the more diverse electorate of 2019 Alberta will receive his personal reformation—with understanding, skepticism, or indifference—remains to be seen.

Taylor Lambert is a Calgary writer and the author of Darwin's Moving, which won the 2018 City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize.

Correction: We originally stated that same-sex marriage became legal in Alberta in 2002; in fact it was 2005. The story has been updated accordingly.

Support in-depth Calgary journalism.

Sign Me Up!We connect Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism—but can't do this alone! We rely on our readers and listeners to fund our work. Join us by becoming a Sprawl member today!