Photo: iStock/erlucho

My cabbie is a doctor: The problem of skill-waste in Canada

Educated professionals deserve more than low incomes.

Earlier this year while visiting Edmonton I called for a cab to transport me. A personable middle-aged man, probably in his late 50s, picked me up. The easygoing chap and I began talking about our immigrant experiences in Canada.

Over 30 years ago, he and his friends fled Afghanistan, a country then plagued by civil war, and ended up in a refugee camp in Pakistan.

Back in Afghanistan, he and his buddies obtained bachelor’s degrees in different agricultural disciplines from a local university.

After a few years in the refugee camp, Canada accepted the cabbie’s refugee application, while his friends’ were accepted by the US.

I asked him why he was driving a cab, since he had arrived in Canada decades ago, degree in hand.

He explained that upon arrival in Canada, he found out his degree was not recognized here, and getting the equivalency was going to be costly. He still had an elderly mother to take care of back home and just wouldn’t be able to save enough money to get his credentials recognized.

The country’s system for providing meaningful employment to imported talent is flawed.

Meanwhile, his buddies in the US had no issue finding work in their fields because some of their university courses had been offered in partnership with an American university, and thus their degrees were recognized in the US.

In his facial expression I saw the disappointment he felt. His fate had been decided by the education he thought would “liberate him.”

When I parted ways with the jolly cabbie, I wondered how many more like him are out there—professionals reduced to low-income work as a result of the challenges and expenses they have to overcome in Canada.

Canada’s catch-22

While Canada ranks high among immigrant-friendly countries, the country’s system for providing meaningful employment to imported talent is flawed, and often shortchanges the internationally educated professional (IEP).

Due to an aging population and labour shortages, there is no question that Canada needs immigrants. Yet foreign credential recognition remains one of the major challenges new immigrants face.

But this isn't a new problem. In 2010, René Houle and Lohouaria Yssaad revealed in a report that “almost 9 out of 10 newcomers with credentials above a high school diploma had a university degree at the time of landing in Canada.”

Canada could gain $13.4 to $17 billion through better-employed human capital resulting from enhanced learning recognition.

IEPs whose professions are regulated in Canada, such as pharmacists, dentists, physicians, accountants, nurses, teachers, architects and engineers, have to follow a licensing process that is usually lengthy and expensive. This results in a loss of skills, talent and revenue for Canada.

In 2016, only 5% of new immigrants seeking credential recognition were gainfully employed. A report by the Conference Board of Canada reveals that “Canada could gain $13.4 to $17 billion through better-employed human capital resulting from enhanced learning recognition.”

“When learning is unrecognized, people earn less in the labour market through either unemployment or underemployment… Canada needs a world-class learning recognition system because it depends on a mobile labour force whose learning credentials are issued in a different place from where they work,” the report states.

Many IEPs end up underemployed or working survival jobs just to put food on the table, grapple with high childcare costs, and send money back home to support family members. This leaves them with barely any savings to get their credentials recognized and unable to get a better paying job.

It’s a catch-22.

The strain on healthcare workers could be minimized if licensing of internationally trained professionals were quicker and more affordable.

Aware of these hurdles, in 2013 the federal government launched the Foreign Recognition Program which provides funding to provinces and organizations running foreign credential recognition programs.

More recently, in Alberta, Jason Kenney’s government proposed Bill 11, the Fair Registration Practices Act, which came into force in March.

This act will see the creation of the Fairness to Newcomers Office and promises to speed up the licensing process, reduce red tape and remove some of the barriers that bind newcomers to underemployment and prevent them from getting ahead in Canada.

The office will also serve an accountability function to regulatory bodies which will be mandated to provide reports on their fair registration practices to the minister of the act.

The proof will be in the pudding with this one.

Caught in the underemployment maze

Now that the world is fighting a global pandemic, the strain on healthcare workers could be minimized if licensing of internationally trained professionals were quicker and more affordable.

One of my friends, a physician from Nigeria, arrived in Alberta in 2019. She is a community medicine and public health specialist with 13 years of practice. She currently works at a local postal service while pursuing her licensing.

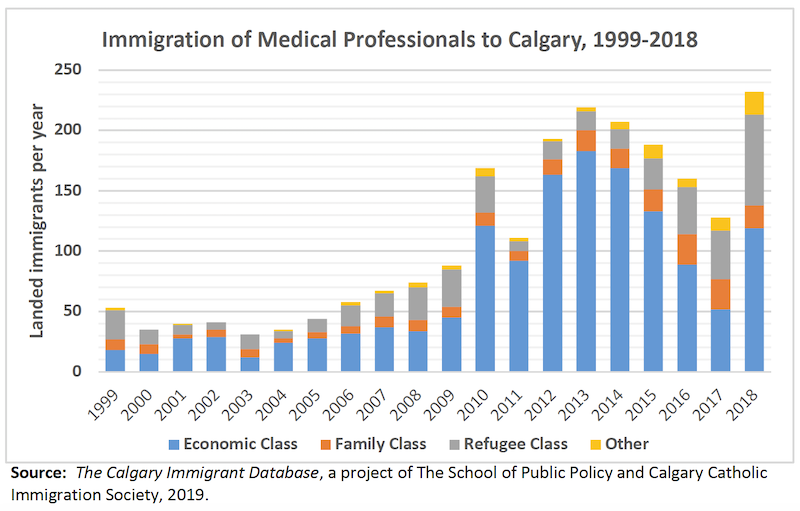

In 2018, 300 immigrant physicians arrived in Alberta—with 70 of them in Calgary, according to the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

Province-wide, the Alberta International Medical Graduates Association (AIMGA) currently has over 1,000 members. Although many of them are pursuing Canadian certification as medical doctors, others are looking into alternative careers in healthcare—this, as a result of the lengthy and costly process.

To pass recertification, international medical graduates (IMG)—like all medical practitioners in Canada—must complete a residency in a Canadian hospital.

According to the Canadian Residency Matching Service, in 2019, 2,835 medical graduates were matched to a residency program in Canada. While 94.5% of Canadian graduates were matched to a residency program, 50% of IMGs remained unmatched.

As any Canadian cab commuter can confirm, many cab drivers have remarkable academic qualifications and work experience in their fields.

Right now, there shouldn’t be any IEPs caught in the underemployment maze.

The medically qualified should be the boots on the ground, fulfilling their oaths by saving lives on the frontlines during this fight against a global pandemic, while the rest should be soaring and reaching the peak of their careers in Canada.

Onai Petra Paswani-Abote is a journalist with a broadcast major. She has worked at the Calgary Herald and now works in the non-profit sector in Calgary.

Now more than ever, we need strong independent journalism in Alberta. That's what The Sprawl is here for! When you become a Sprawl member, it means our writers, cartoonists and photographers can do more of the journalism we need right now. Become a Sprawl member today!

Support in-depth Calgary journalism.

Sign Me Up!We connect Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism—but can't do this alone! We rely on our readers and listeners to fund our work. Join us by becoming a Sprawl member today!