Photo: Elections Alberta

Reading the electoral tea leaves is a fraught business at the best of times.

Remember the 2012 campaign, when Danielle Smith’s Wildrose Party was predicted by pollsters, just days before the election, to sweep to a tremendous victory? Or 2017, when Naheed Nenshi was heading to sure defeat? (Those elections, uh, didn’t quite turn out that way.)

Politics is always a wily beast, but Alberta’s current political landscape has changed in ways we have yet to fully understand—and that makes predicting this election a fool’s errand.

“I think it’s a unique election,” says Alvin Finkel, professor emeritus of history at Athabasca University. “In the past, the conservative party was so dominant, essentially elections were coronations.”

Before it happened, no one could foresee the complete collapse of the four-decade PC dynasty. Before it happened, no one could imagine an NDP majority government in Alberta being elected with support that, although concentrated in the two big cities, was broad enough to win seats in rural and small-city ridings.

In short, Alberta’s politics have been upended in surprising ways that make conventional wisdom less reliable.

It’s difficult to place this election in the context of previous Alberta campaigns. Change elections have been relatively scarce in Alberta, given the province’s history of political dynasties.

That means we’re left with few and distant case studies that bear little resemblance to modern Alberta.

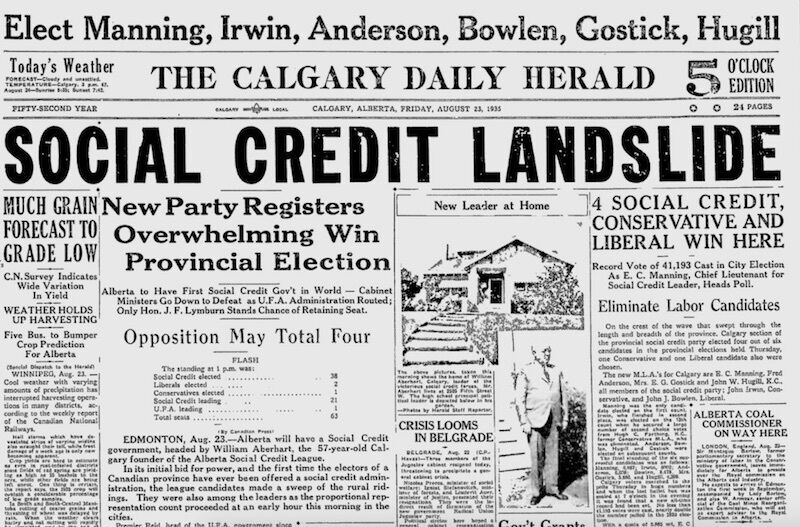

Forget 1921 or 1935, when brand-new upstart parties (United Farmers and Social Credit, respectively) unexpectedly swept to power—Alberta is a drastically different place than 1971, when Peter Lougheed ushered in the Progressive Conservative era, or even 1993, when Ralph Klein’s right-wing populism brought him to office.

“You can find some similarities [to 1921 or 1935], but I think they fall apart,” says Finkel.

One such similarity he offers is between the campaign promises of Jason Kenney’s UCP and the 1935 campaign of William Aberhart’s SoCreds—not in substance so much as overselling.

Finkel says that while the SoCreds offered an “interventionist program” that involved controlling banks and currency in ways they had no power to actually do, “the UCP is promising a market-based program that involves things they can’t do — they can’t control the price of oil, they can’t control what oil producers internationally are going to do.”

Ditto for unilaterally implementing equalization changes or pipelines.

“The similarity with 1935 would be that you have a party telling the people of Alberta that the provincial government could have powers that it actually doesn’t have,” says Finkel.

The Alberta NDP’s 2015 victory came with many adjectives: historic, in part because it marked the end of the PC dynasty; groundbreaking, because it proved a centre-left party could succeed in Alberta.

One other legacy we might one day affix to that campaign: realignment. As in, a fundamental shift in the political reality of the province that lasts well beyond one election cycle.

Prior to 2015, just four parties ever formed government in Alberta over 110 years, all for lengthy unbroken stretches, none ever returning to power once defeated.

It’s possible that the 2015 election changed all that. Perhaps, regardless of who forms the next government, Alberta will no longer dominated by a single party but have a somewhat more balanced political field, with two primary parties who alternate power.

The UCP is promising a market-based program that involves things they can’t do — they can’t control the price of oil.

“Given our history of long periods of one-party dominance, this makes the 2019 election and the legislative dynamics after the election potentially game-changing,” wrote Anthony Sayers, associate professor of political science at the University of Calgary, in an email toThe Sprawl.

“It also means that we may see after the election two parties with distinct urban bases: Edmonton for the NDP and Calgary for the UCP.”

Finkel believes the landscape has already shifted, no matter who forms the next government.

“I think regardless of the outcome of this election,” he says, “Alberta has become more like the other Western provinces—that is, the politics have polarized between a modestly left-learning NDP and a right-wing party.

Jason Kenney has referred to the NDP as an “accidental government.” While the “orange chinook” has indeed faded since 2015—the party hasn't led a poll since—the implication that a centre-left government is an aberration that requires correction seems to be not just a political talking point, but a deeply-felt truth among some on the right.

The NDP governing Alberta is, as Jen Gerson aptly put it, “a psychic wound for conservatives.”

But the notion that electing a UCP government would be “restoring” anything doesn’t quite fit. The party is the result of a merger between the old Progressive Conservative and Wildrose parties, but the new party is more Wildrose than PC. The Red Toryism of the PCs has faded.

The Progressive Conservatives’ tremendous longevity can be partly attributed to occupying the mushy middle of the political spectrum.

“The UCP is really the Wildrose party, having captured the PCs,” says Finkel. “When those parties nominally united, you had one party that had far more members than the other, essentially taking over.”

The Progressive Conservatives’ tremendous longevity can be partly attributed to occupying the mushy middle of the political spectrum, tacking one way or another to appeal to different groups as needed. They never strayed too far or too long from the supposedly pragmatic, middle-of-the-road politics that appeal to many middle-class Albertans, particularly in the cities and suburbs.

The Wildrose Party, on the other hand, was never known for successfully moderating its far-right impulses—arguably one of the reasons it never gained power.

Whether the more extreme elements of the UCP can be successfully packaged and sold to a majority of mainstream Albertans is a big question.

Perhaps the most defining aspect of the 2019 Alberta election is the fact that the two main parties are presenting such widely different views of Alberta’s present and future—to the point that they might be fundamentally irreconcilable.

The NDP has governed largely from the moderate centre-left, with only a handful of progressive policies, none of them terribly radical. That’s the same approach seen in their re-election platform, with increases in social spending and pledges to ban conversion therapy, fight climate change and attempt to diversify the economy.

The emotional centre of a good chunk of the UCP argument is that everything would be fine if you just left things the way they used to be.

Though most overtly applied to climate change and economic concerns—the so-called “job-killing carbon tax,” for example—successive scandals around multiple UCP candidates espousing racist or homophobic views suggest that the door has been left open for broader interpretations of “the way things used to be.”’

The NDP has governed largely from the moderate centre-left, with only a handful of progressive policies, none of them terribly radical.

“They are irreconcilable,” says Finkel of the two parties’ worldviews.

“You’ve got one party whose vision of government is to ensure that people have adequate health, education and social programming. Then you have the other party, the UCP, wanting to cut all that and claiming that the role of the provincial government is to lure investors at the expense of social programs.”

Economic woes may be front and centre in this campaign, but given the wide gap between the NDP and UCP’s respective visions of society, the threat of climate change, and the future of the province, the choice voters make may tell us a good deal about Alberta’s values and divisions.

Regardless of the election’s outcome, Finkel believes we’re already in a new era of Alberta politics, where the NDP and UCP trade power with comparative regularity while the electorate remains polarized.

“That question of the role of provincial government,” he says, “is going to stay with us.”

Taylor Lambert is a Calgary writer and the author of Darwin's Moving, which won the 2018 City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize.

The Sprawl is crowdfunded, ad-free and made in Calgary. Become a Sprawl member today and support independent, ad-free Calgary journalism!

Support in-depth Calgary journalism.

Sign Me Up!We connect Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism—but can't do this alone! We rely on our readers and listeners to fund our work. Join us by becoming a Sprawl member today!